Multi-Paxos: Building a Simple Replicated Log in Python

Marton Trencseni - Sun 07 December 2025 - Distributed

Introduction

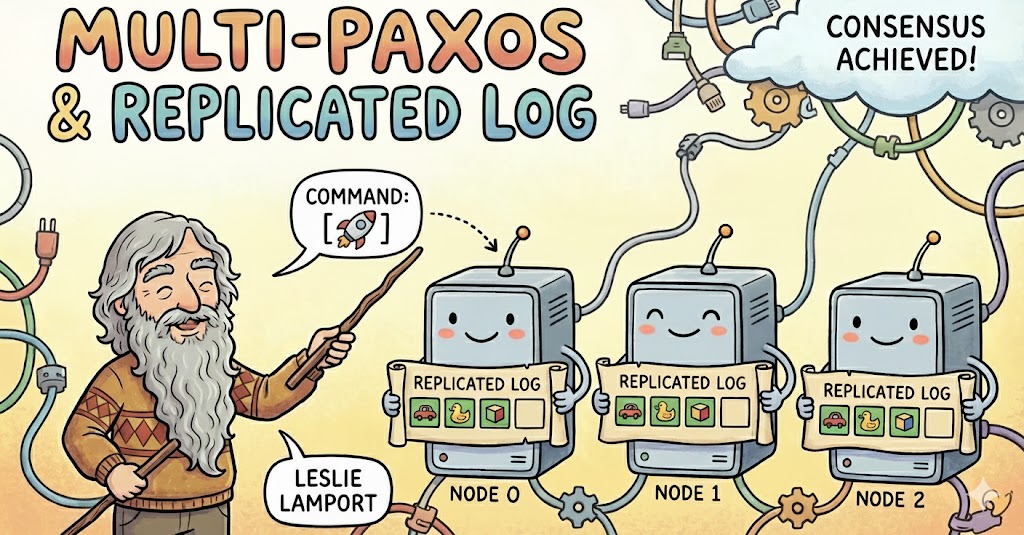

In the previous post we built a compact, 200-line implementation of Lamport’s Paxos algorithm. That implementation did exactly one thing: choose a single value. It demonstrated the core mechanics of Paxos — the roles of proposers, acceptors, and learners; the two-phase protocol; and the safety guarantees that make it such a foundational distributed algorithm.

But single-shot consensus is not enough to build anything useful. Real systems need a sequence of agreed-upon values: write operations on a key-value store, log entries in a database, configuration updates, or anything else that modifies shared replicated state. This idea — that consensus is run over and over to produce a replicated log of commands — is the foundation of State Machine Replication (SMR) and it is how practical systems achieve fault-tolerant consistency.

This post builds a Multi-Paxos version on top of the previous simple implementation. It's still intentionally compact and easy to read, but now the system maintains a replicated log, executes commands locally on a per-replica toy database stand-in, keeps track of per-round Paxos state, and allows lagging nodes to catch up automatically. The goal remains the same: illuminate how Paxos actually behaves rather than present a production grade implementation.

In this implementation, as in the previous one, nodes do not persist their state to disk. This technically breaks the assumptions of Paxos: even if a majority previously agreed on a value, a node restart would erase its acceptor state and cause it to forget past promises and accepted proposals. I intentionally keep the implementation this way to keep the code small, readable, and pedagogical. The code is on Github.

Note: In the literature, Multi-Paxos refers specifically to the leader-optimized version of Paxos, where a stable leader performs Phase 1 (prepare) once and then executes many consecutive Phase 2 rounds, dramatically reducing overhead. That optimization is not implemented in this article. Here, I use “Multi-Paxos” in a more informal sense to mean running multiple full Paxos rounds in succession to build a replicated log. In a later post I’ll add leader election and the Phase-1-skipping optimization that makes Multi-Paxos practical in real systems.

Rounds of Paxos

In the simple version, only one value could ever be chosen. That value was essentially a write-once register. The natural next step is to repeat Paxos for multiple rounds, to get a sequence of write-once registers, an append-only replicated log. Each round (also called a slot) chooses one command, and all learners apply the same command to their local state, maintaining a consistent database.

To keep things simple, each command is a Python statement such as:

li = []

li += [1, 2]

li += [3, 4]

i = 0

i = 42

These commands are executed with exec() inside the learner, modifying a simple per-node dict used as our "database". Obviously this is not safe in real systems, but for a teaching implementation it is a wonderfully transparent way to show how replicated logs drive local state transitions.

Rounds are indexed with integers: round_id = 0, 1, 2 .. Each round runs its own instance of Paxos with independent acceptor/learner state. When a round completes and a value is chosen, nodes advance to the next round. Taken together, the chosen values form a log of commands which all nodes execute in the same order, producing deterministic, consistent state.

The code keeps the three Paxos roles but now stores state on a per-round basis:

- Acceptor:

rounds[round_id].promised_n,accepted_n,accepted_value. - Learner:

rounds[round_id].chosen_value. - Proposer: unchanged — it simply passes

round_idinto all prepare/propose/learn requests.

A new endpoint /command triggers one new Paxos round, choosing and applying a Python command.

To support multi-round operation, several new REST endpoints were added:

/current

Returns the node’s current round number — the next Paxos slot it expects to fill.

/fetch?round_id=i

Returns the command chosen for round i, if any. This is how a lagging node can ask a peer:

“Tell me what was decided in round 42.”

/db

Prints the node's key-value database.

Below is the code for the modified learner, which stores per-round chosen values and executes newly learned values against the local database:

class PaxosLearner:

def __init__(self, db, db_lock):

self._lock = threading.Lock()

self.rounds = {} # round_id -> SimpleNamespace(chosen_value)

self.db = db

self.db_lock = db_lock

def _get_round_state(self, round_id):

if round_id not in self.rounds:

self.rounds[round_id] = SimpleNamespace(chosen_value=None)

return self.rounds[round_id]

def learn(self, round_id, command_str):

with self._lock:

st = self._get_round_state(round_id)

# Paxos should never learn two different values for the same round

if st.chosen_value is not None:

assert st.chosen_value == command_str

return True, st

st.chosen_value = command_str

# apply the command to the local "database"

# NOTE: this uses exec and is obviously unsafe in real life.

with self.db_lock:

exec(command_str, {}, self.db)

return True, st

Catching up lagging nodes

If a node crashes, falls behind, or simply processes commands slowly, it can reconnect and catch up. This is an essential property of all replicated log systems: the log is the ground truth, not the nodes’ current memory.

To enable this, the nodes run a tiny background thread:

- Every second, a node pings other nodes’

/currentendpoint. - If a peer is ahead (e.g., at round 10 while this node is at 7), it retrieves rounds 7, 8, and 9 via

/fetch. - For each retrieved value, it calls the learner locally — as if the value had just been chosen.

- Once caught up, it advances its own

current_roundpointer.

The implementation is below:

def try_catchup():

# Background loop: poll peers' /current and, if they are ahead, pull

# missing rounds via /fetch and apply them locally via learner.learn()

while True:

time.sleep(1.0)

local_round = get_current_round()

for peer in peers:

# don't query self

if peer.endswith(str(port)):

continue

try:

r = requests.get(f"{peer}/current", timeout=1.0)

if r.status_code != 200:

continue

peer_round = r.json().get("round_id", 0)

except Exception:

continue

if peer_round > local_round:

for rid in range(local_round, peer_round):

try:

resp = requests.get(f"{peer}/fetch", params={"round_id": rid}, timeout=1.0)

if resp.status_code != 200:

continue

data = resp.json()

if not data.get("success"):

continue

value = data.get("value")

learner.learn(rid, value)

except Exception:

continue

advance_round(peer_round)

local_round = peer_round

if __name__ == "__main__":

# start background sync thread

t = threading.Thread(target=try_catchup, daemon=True)

t.start()

...

This simple loop reproduces the basic idea behind log synchronization in practical consensus systems: pull missing decisions from peers and apply them in order. There is no heartbeating, no leader election, and no Multi-Paxos “leader optimization,” but the toy implementation does capture the essence of a replicated, fault-tolerant log.

A subtle but essential point in Multi-Paxos is the difference between choosing a value and learning a value. Choosing a value requires a majority of nodes: at least $ f+1 $ out of $ 2f+1 $. This ensures the safety of Paxos, because any two majorities intersect. But once a value has already been chosen by a majority, learning that value does not require a majority at all. A lagging node does not re-run Paxos; it simply asks any peer what the chosen value for a given round was. Paxos is quorum-heavy during decision-making, but extremely lightweight during catchup.

This raises a natural question: how can it be safe for a node to trust the response of just one peer? In crash-fault Paxos we assume nodes may be offline, slow, or inconsistent in availability — but not malicious. A node is therefore permitted to believe another node’s report about a past consensus decision. The safety guarantee comes from the fact that no node can produce a learned value unless it was previously accepted by a majority, not from proving that the reporting peer is honest in a Byzantine sense.

Consider a concrete example. Two nodes successfully run rounds 0 through 100 while the third node is offline. Later, only one of those nodes is reachable when the third node returns. Even though only a minority is online at this moment, the lagging node can catch up entirely by querying /fetch on that single peer. It trusts the peer’s answers because the system assumes crash faults, not malicious ones, and because Paxos ensures that any value that could be reported by a correct node must have been chosen by a quorum earlier. This asymmetry — quorums for choosing, but no quorums for catching up — is one of the practical strengths of Paxos.

Execution path

A full write path now looks like this:

- Client sends a JSON command to

/command. - The node, acting as proposer, runs a Paxos round for the current slot, using the

/prepare,/propose, and/learnendpoints. - Acceptors respond with phase 1 and phase 2 logic as in the original version.

- A majority acceptance results in a chosen command.

- All nodes learn and apply the change to their local database.

- The round advances.

- If a node was offline previously and needs to catch up, it uses the

/currentand/fetchendpoints. - A client can observe the current state of the database on

/db.

Each command is a deterministic state change, and all nodes execute the same commands in the same order, yielding identical state — the defining property of State Machine Replication.

The Multi-Paxos structure here is intentionally stripped down, but it demonstrates a complete path from:

"Here’s one value chosen by Paxos"

to

"Here is an infinite log of values chosen by Paxos, keeping all nodes consistent."

Even this tiny version shows the core architectural pattern used in fault-tolerant databases, distributed key-value stores, scheduling systems, lock services, and coordination layers.

Adding more sophistication — such as durable storage of accepted values, leader election to eliminate repeated Phase 1 rounds, batching, log truncation, snapshotting, or network partitions — is all incremental on this same foundation. The point is that once you understand single Paxos, Multi-Paxos is almost anticlimactic: it’s just “run Paxos again and again, keeping the slots straight.”

Sample execution

To see the implementation in action, imagine starting with a 3 node cluster, but only node 0 and 1 are up. Both come up empty: their db dicts are {} and their current_round is 0. A client now sends a series of commands to node 0 via /command:

1: li = []

2: li += [1, 2]

3: li += [3, 4]

4: i = 0

Each /command call triggers a new Paxos round for the current slot: round 0 chooses li = [], round 1 chooses li += [1, 2], round 2 chooses li += [3, 4], round 3 chooses i = 0. For each round, node 0 acts as proposer, talks to both nodes’ acceptors, and when a majority accepts, broadcasts the chosen command to /learn on both 0 and 1. The learners execute the commands with exec() against their local db. After these four rounds, /db on node 0 and node 1 both return the same JSON:

{

"current_round": 4,

"db": {

"i": 0,

"li": [1, 2, 3, 4]

}

}

At this point node 0 goes offline. Node 2 now comes up for the first time, with an empty db and current_round = 0. Even though only node 1 is reachable (no majority), node 2 can still catch up: its background sync loop polls /current on node 1, sees that node 1 is at round 4, and then iterates round_id = 0..3, calling /fetch?round_id=i on node 1. For each round, node 1 returns the chosen command; node 2 calls its own learner with that command, which executes it locally. After this loop, node 2 has applied the same four commands and advances its current_round to 4. Node 1 and node 2 now have matching /db outputs.

A client then sends a new command i = 42 to node 2 via /command. This becomes round 4: node 2 runs Paxos with nodes 1 and 2, the command is chosen, /learn is broadcast, and both update their databases so that i is now 42. Later, node 0 comes back online. It starts with stale state (current_round = 4, i = 0), but its sync loop quickly notices that a peer (say node 1) is at current_round = 5. Node 0 retrieves round 4 via /fetch, learns i = 42, executes it locally, and advances to round 5.

At this point, all three nodes have converged, and /db on any node returns:

{

"current_round": 5,

"db": {

"i": 42,

"li": [1, 2, 3, 4]

}

}

Strong consistency is preserved: once a command is chosen, all nodes eventually learn and apply the same sequence of commands, and their databases match exactly once they reach the same round.

Network splits and Consistency

A replicated-log Paxos system provides strong consistency in the precise sense that the cluster will never diverge: for any round, only one value can ever be chosen, and every node that reaches that round will eventually execute exactly the same command. The log is a single, linear sequence, and Paxos ensures that no fork, branch, or conflicting history can arise. However, strong consistency at the log level does not imply that all nodes always present identical state to clients at the moment of a read. Nodes may be at different points in the log—some may be fully caught up, while others may be lagging because of crashes, slow recovery, or temporary partitions. Such nodes are not inconsistent in the sense of violating correctness; they are merely behind. They will converge as soon as they apply the missing commands.

This distinction matters in real applications. Suppose client A writes a value via /command, and the operation completes successfully on the node it contacted (and a majority of the cluster). Paxos guarantees that this write has a well-defined position in the replicated log and will become visible to any node that reaches that round. But if client A then communicates out-of-band with client B, and client B asks a different node for a read, that second node might still be behind (for example, it could be split off from the majority of the cluster) — even though the system is strongly consistent in the formal sense. Client B might observe older state unless the system provides a way to coordinate visibility.

To handle this, nodes can return the round_id of the chosen command in the /command response. Client A can pass this round_id to client B in their backchannel. When B later talks to any node in the cluster (even one that was partitioned or lagging), it can insist on reading only after the node’s /current round is at least as large as the round ID carried from client A. If the contacted node is behind, client B can either retry later, or trigger a catchup flow explicitly, or look for another node to talk to. This pattern aligns the semantics of strong consistency with the realities of partial visibility during transient failures: the system never diverges, but clients can still ensure that reads observe the effects of specific writes by synchronizing on log positions rather than on wall-clock time or assumptions about which node is up to date.

Further improvements

There are many natural extensions from here:

- Use real database operations instead of Python

exec. - Add leader optimization: one proposer runs Phase 1 once, then arbitrates Phase 2 for many rounds.

- Add persistence, so acceptor promises survive crashes.

- Add log compaction or snapshots.

- Replace HTTP with a message bus or RPC framework.

- Integrate random backoff or retries for competing proposers.

But even before all that, this version already demonstrates the essential step from “Paxos chooses a value” to “Paxos drives a replicated state machine,” which is what makes consensus algorithms so central to modern distributed systems architecture.

Conclusion

Multi-Paxos illustrates a powerful idea: once you understand how a single Paxos instance chooses a value safely, extending it to a replicated log is conceptually straightforward. Each round becomes one slot in a deterministic sequence of commands, and every node that eventually executes the full prefix of the log will converge to the same state. The algorithm remains simple in structure — two phases, majority quorums, and per-round acceptor and learner state — yet it supports a fully fault-tolerant, strongly consistent replicated state machine that can recover from crashes or partitions without losing correctness.

At the same time, the multi-round setting exposes the practical subtleties that real systems must address: nodes may fall behind, clients may require visibility guarantees across requests, and catchup becomes a first-class mechanism for maintaining consistency in the presence of partial failures. Even with these complexities, the 2.0 implementation remains deliberately compact, showing how far one can go with a minimal amount of code. In later extensions we can add durability, leadership, batching, snapshots, or real database operations — but the essential shape is already here: a cluster that can keep unanimous, linearized agreement even when individual nodes cannot.