Why I don't live in Hungary

Marton Trencseni - Wed 07 August 2024 - Meta

Introduction

In February 2016, I made a life-changing decision to leave Hungary and seek opportunities abroad, starting in London and later moving to Dubai. This essay explores the multitude of reasons behind my choice and why I have no immediate plans to return to Hungary. From the political climate and economic conditions to education and quality of life, I will delve into the factors that have influenced my decision to build a future outside of Hungary.

Politics and democracy

One of the major factors is poor politics in Hungary, the social mood and attitudes this creates, and the future it foreshadows. Since 2010, Fidesz has been the ruling party in Hungary with a two-thirds majority in parliament, which allows them to change the constitution at will. Also, since 2015, there has been an almost-continuous state of emergency, initially because of "migration," then Covid, and later for various made-up reasons. This means that laws can be and are passed by the government bypassing parliament—not that laws could be blocked in parliament, since the party has a two-thirds majority anyway—but it means laws can change and do change overnight.

I don't want to write too much about this, since it is common knowledge. Fidesz has used this amazing opportunity of a two-thirds majority not to create progress and unity in Hungary, but instead to create division. This creates specific problems at the individual level for me. Fidesz has taken over a significant portion of media surfaces in Hungary and essentially converted them to be state-owned and state-run, through various cronies who can be tied to the prime minister and his inner circle. This state-run media network poisons their voters' minds with alt-right content and political hate speech, similar to alt-right Trumpist propaganda in the US. This creates a situation where about half the country (again, similar to the US) is hopelessly xenophobic (often against groups of people they've never even met), pro-Russia (even though remembering 1956, when Hungarians revolted against Soviet Russian occupation, is our biggest national remembrance day), anti-civil rights, etc.—even though Fidesz's actual politics do not favor such people and keep them in poverty (both economic and intellectual). This major segment of the population has completely lost their ability for independent and critical thinking (if they ever had it) and have adopted an identity and loyalty tied to Viktor Orbán and Fidesz, often over their families (e.g., my mother). So, if I were to live in Hungary, I'd have to face the fact that about half of my friends and family are brainwashed, and there's nothing I can do about it—since Fidesz has taken over the government, their funds available for propaganda are practically unlimited, amounting to a measurable fraction of Hungary's GDP. Also, if my son were to go to school in Hungary, about half of his teachers would be brainwashed Fidesz voters, which is unacceptable to me.

The other side of the coin is the economic result of Fidesz's rule. Hungary joined the EU in 2004 and has been a member ever since. As an EU country that is less developed than Western countries such as Germany and France, Hungary has received significant aid from the EU, totaling 83 billion euros, about 4x what Hungary has itself put into the EU. About 20% of Hungarian GDP is due to the EU. Additionally, the 10 years between 2010 and 2020 were a time of global economic growth and prosperity (in the West). However, Fidesz has been unable to leverage this historic opportunity and has created an inefficient economy of corruption and backward investment, which has resulted in Hungary sliding back to be one of the worst-performing countries in the EU, in all major indicators: spending power, standards of living, corruption, academic performance of students, etc. Viktor Orbán's family members, friends, and neighbors have accumulated tens of billions of dollars of personal wealth from redirecting state money to their companies, and since Fidesz can change laws at will, this was mostly done legally and is thus irreversible. Even worse, much of the population has accepted that this is normal, this is just how things are: in Hungary, people in power steal billions of dollars, and there's nothing anybody can do about it, so it's best not to even worry or talk about it.

It's only fair to point out that historically Hungary has always lagged behind Western countries such as Germany and France. Even if we had the best politics since 2010 (or since 1990), we would still be behind these countries, since change and progress at the national scale take a long time. However, this is irrelevant because we're not catching up at all; in fact, we're sliding back even compared to our peers, i.e., other Eastern European countries.

Unfortunately, given the situation I described in a nutshell above, I'm quite pessimistic about the next 20 years in Hungary. The psychological and mental damage Viktor Orbán and Fidesz have created will take many years—maybe one or two generations—to decay, assuming Hungary can get on a better, positively-sloped track, which is currently not even in sight. Also, it's not clear how Hungary could stay on a good track for any length of time, given the psychological damage created: even a good government would make mistakes and would face external challenges (e.g., recession), which would cause setbacks, and then reversion to Fidesz or similar forces. It's not clear when or how such a change could even start. Fidesz has legally made changes to the political and electoral system (not detailed here) that make it very hard to vote them out. The major factors:

- state-wide Fidesz propaganda running on with state funds or national news outlets

- redrawn electoral maps, i.e., gerrymandering

- various thresholds creating non-linearity in Fidesz's favor (e.g., small parties have to cross a 5% - vote threshold; otherwise, those votes get lost, effectively lowering the total count of votes)

Overall, this creates a situation where, although Fidesz only gets about half of the popular vote, they get more than two-thirds of parliamentary seats—every single time since 2010.

Looking at the opposition parties and votes, the situation does not improve. The two biggest challengers to Fidesz since 2010 have been Jobbik, an ever-more far-right and xenophobic party, and now Tisza, a party run by an ex-Fidesz client. I usually take a tally of votes after each election, estimating what percentage of overall votes go to unacceptable, xenophobic, hate-mongering right or far-right parties, and during the earlier election, adding up Fidesz, Jobbik, and Mi Hazánk votes yielded a sum of 75%. That is not a country I want to bet on.

One of the core ideas of data science and algorithmic trading is backtesting. Backtesting means that when we come up with an idea for a prediction algorithm (e.g., if stock X goes down on day T, it will surely go up on day T+1), we first test it on historic data and see how it would perform. There are all sorts of details and caveats, but that's the basic idea. I find that this idea is also useful in planning my own personal future: political backtesting! Unfortunately, the results are not great: if I look at the last 150 years of history in Hungary, it was never a good idea to live in Hungary. There was always some sort of major crash on the horizon, which often wiped out both people and fortunes and created a hard reset for many. First, there was the time leading up to the First World War, which, similar to today, had poor Hungarian politics with naive foreign politics, leading to fantasies about the international balance of power and how the war would go, ultimately resulting in a crash for the entire country, with Hungary losing two-thirds of its land area (Trianon). Then, between the two world wars, we had more poor politics, resulting in Hungary aligning with Nazi Germany in hopes of getting back its lost territories, which we did temporarily. This alliance with Hitler also included Hungary shipping off its own (Jewish) citizens to be killed, but ultimately it led to another economic and human crash and reversal of territorial gains. To make things worse, Hungary was occupied by the Soviets, which led to 40 years of communism in Hungary, which finally ended in 1989. During these years, it was never a good time to live in Hungary (as compared to other options, e.g., emigrate to the US); the average family was always living in (relatively) poor conditions and/or approaching another crash. In 1989, Hungary started on the path of democracy, but here we are in 2024, and as I described above, we are not in a good place—we are one of the least attractive countries in the EU in terms of metrics.

Marton, but wait! You live in Dubai, it's not even a democracy! And you will never get citizenship there anyway (the UAE does not naturalize citizens). And even if it were, you couldn't vote anyway! That is true and something I think about a lot!

My relationship to democracy is quite theoretical: I was born in 1981, so the first Hungarian parliamentary election where I was eligible to vote was in 2002, and then every four years, six times total—but I have never voted for the party that won! This is quite unlike US politics, where most of the population votes for either the Democrats or the Republicans, and these two major parties take turns running the country. So, in this sense—unlike me—the average American will see their candidate running the country about half the time, or, for about half of their lifetime. For this reason, specifically for me, the fact that I live in a country where I can't vote doesn't bother me much, because in the one country where I can vote, my vote never counted, and given that I'm not a Fidesz (or Tisza) voter, it doesn't look like it could count anytime soon.

Living in Dubai is very different from living in Hungary or other European-style countries, which is why matters around democracy or voting are not an issue for Dubai expats. First of all, services like healthcare and education are already high-quality here, with lots of choices, so there's nothing to politicize on that. They are decidedly non-free, but for expats like myself, they are mostly (e.g., 80% of school fees) paid for by the company I work for, and salaries are very high, so it's not a factor. Roads are already high-quality and constantly maintained, etc. Another interesting factor about living in a city like Dubai is that approximately 80% of the population are expats (from other GCC countries, India, Pakistan, Philippines, Europe, US, Australia, etc.). These expats, although they have vastly different cultural backgrounds and religions, are still a unique subset of their respective local populations: they are the ones who are flexible, open to new ideas and opportunities, willing (and able) to move to another country and make a life there. There are countless points of disagreement between me and my friends from various countries, but we fundamentally all agree that life is full of interesting people and opportunities, we have to be open to them, and we have to make our own fortune—but the majority of the Hungarian population does not have this world view.

The situation I described in a nutshell above from my personal perspective has been discussed extensively in Hungarian media. A good english language overview is the report 20 years in the EU: Hungary rues missed opportunities, which starts with the following quote:

Anniversaries come and go, but Viktor Orban's government has been busy ignoring them.

Twenty-five years of NATO membership passed almost unnoticed in March, and the country's leaders are making no fuss about Hungary’s 20th birthday in the EU on May 1. Perhaps with good reason: there is little to celebrate. From a socio-economic perspective, Hungary’s two decades in the EU have been one big missed opportunity. Politically, it's love turned into war.

“We had high hopes. We all expected that EU membership would pave the way for us to quickly catch up with the West,” Geza Jeszenszky, a former Hungarian foreign minister, who presented the country’s application for membership in Athens in April 1994 ... “All the other countries in the region made better use of the generous EU funds and opportunities than we did,” he laments bitterly. “This is a historic sin by Orban – and I hope history will judge him for it.”

Income inequality

The biggest factor is income. My last job in Hungary was at Prezi, a once-high-flying presentation software-as-a-service company. I started in Prezi in 2012 as a Data Engineer and was later promoted to be the Director of Data. This meant that I was managing all Data Engineers and Analysts, including employees in Prezi's San Francisco office. I noticed that I was hiring US employees who were less senior than me on the company's own level system at 3x my Hungarian salary! That's when I started to really think about, am I okay with this?

Companies usually cite the cost of living as the reason why employees in poorer countries get paid less. However, this is a bogus argument since it assumes that people in poorer countries are okay living at a lower standard of living. For example, let's assume rents in a poorer country are lower than in the US—but those lower rents go along with lower-quality apartments, lower-quality buildings, lower-quality roads, lower-quality public transportation, and so on. Because most apartments, buildings, and cities are lower quality, average prices are lower in poor countries, which pulls down the index. Another factor is disposable spend. While working at Prezi I was still single without kids, so my monthly expenses were well below my income as a Director—more than half of my income was disposable. This is also true for similar tech workers in the US; their living expenses [assuming single and no kids] are significantly lower than their income. However, here another inequality comes in: if you have disposable income and want to buy a new MacBook or a new car, those actually cost about 25% more in poorer countries than in the US due to the cost of goods getting there and high import duties and VAT. So, living in a poor country, you have significantly less disposable income, but the optional things you want to buy are more expensive! I first noticed this discrepancy when I watched "owner's reviews" of sports cars such as Porsche 911s on YouTube, and I noticed that the owners were not super-rich millionaires, they were just upper-middle-class people, engineers, etc. But sitting in Hungary, earning $40k after taxes as a Director, buying a $100k car was completely out of reach. The most I ever spent on a car was $10k on a used BMW with 300k mileage.

In 2016, I started working for Facebook in London. It was bizarre that I was doing less than I was at Prezi, where I managed 20+ people, but I was earning 3x more, just because I was sitting in London and not Budapest. Even before Covid I was pretty aggressive about working from home and working from anywhere, so I usually spent three days a week in Facebook's London office because, as a technical individual contributor, I didn't really need to be there. I could have done my job from anywhere in the world. I left Facebook after about two years, so well before the Covid pandemic hit, so I wasn't there when this truth became obvious for everyone: during Covid, employees at big tech companies were working from home, but they had to stay in the same country to keep their salaries—if they moved to a different country (e.g., a Hungarian went home to Hungary, a Pole went home to Poland), their salary got "re-indexed" or lowered. That is the bizarre world we live in.

To conclude, moving from Budapest to London meant a 2-3x multiplier in net income. Then, moving from London to Dubai meant another 2x, simply because Dubai salaries are roughly on par with London gross salaries, but there are no taxes of any kind whatsoever. So overall, Budapest to Dubai is a 5x salary multiplier. The cost of living in Budapest has increased considerably between 2016 and 2024 due to poor governance, so the cost of living in Budapest is approaching that of other major European cities. In summary, I estimate in 2024 the cost of living in Dubai is about 2x, but for a 10x higher quality of life, at 3-5x higher salaries—Dubai wins by a wide margin, it's a no-brainer.

Education

My son was born in December 2018, which means I'm now not just thinking about my own future, but also the future of my son. The two components of this are the quality of education he gets (up to college), and what kind of intellectual and cultural background he gets, in terms of how it sets him up to work in a country with great economic opportunities.

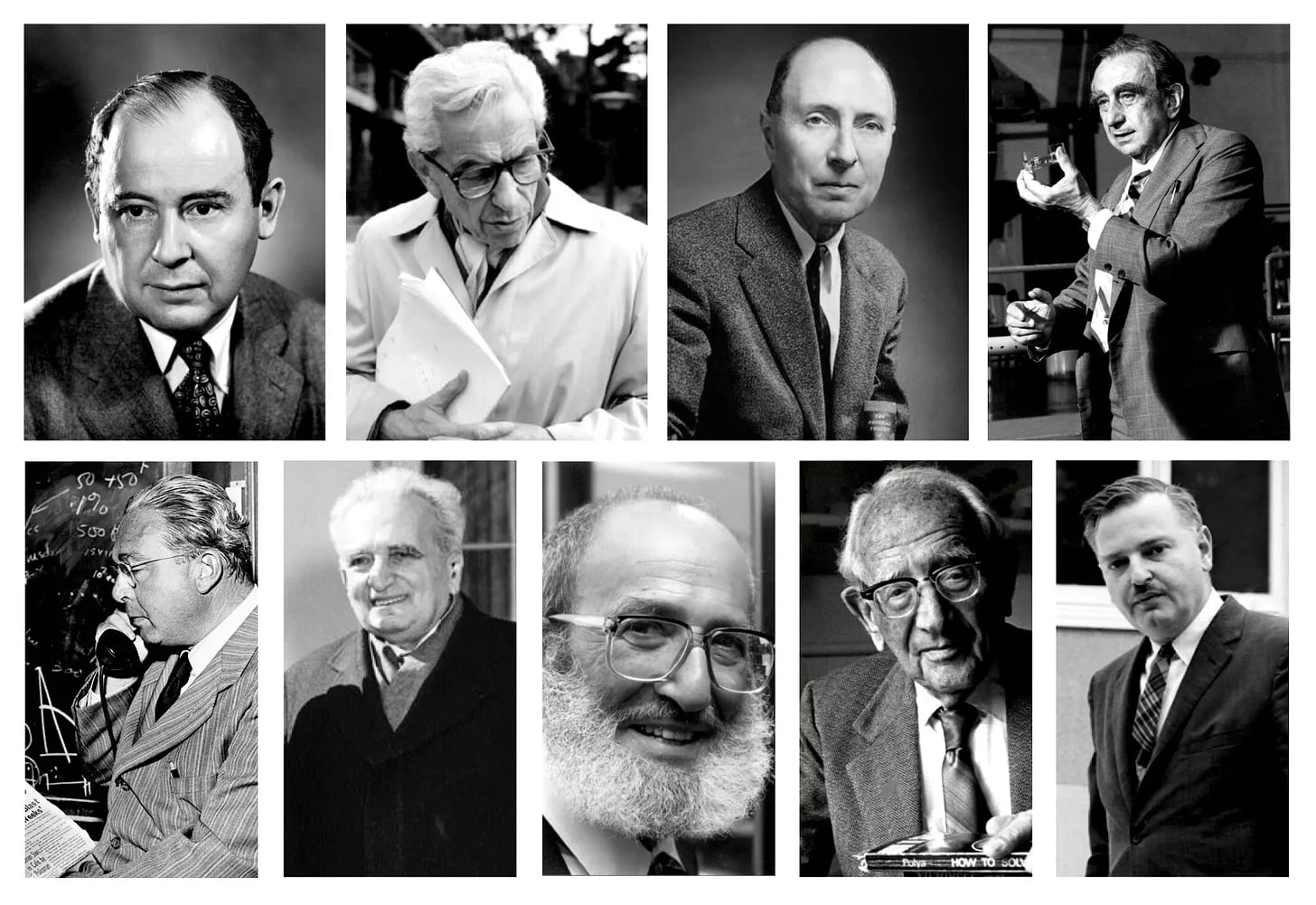

The Hungarian educational system used to be one of the best in the world. In the first half of the twentieth century, many famous physicists in the US were (Jewish) Hungarians who emigrated to the US before World War II to escape persecution. Some examples are the Martians of Budapest: John von Neumann, Paul Erdős, Eugene Wigner, Edward Teller, Leó Szilárd, Theodore von Kármán, and George Polya. They were called The Martians because they were so smart it seemed like they were from Mars. After the Second World War, Hungary became a socialist state and eventually fell behind the West, but math and science education still remained very strong. During my school years, I moved between Hungary, Germany, and the US, and it was always clear that Hungarian education is superior. Although I didn't know and appreciate it at the time, the University education I received in Hungary (MSc. Computer Science at BME from 1999-2004 and MSc. Physics at ELTE from 2002-2008) is also world-class—although these are not recognized brand names, so they're not appreciated on the international job market. I noticed this when I worked at Facebook and worked with some very smart people—they were very smart, driven, and knew more about how to make a social network successful than I did—but there were no differences in the basics. If anything, I probably learned more at University due to our school system's Prussian culture of quantity and rote memorization. Unfortunately, this seems to have changed in the last 20 years. Hungarian school teachers earn abnormally low salaries, even for Hungarian standards. This results in a situation where no sane person chooses this career path, and teachers who can, look for other jobs (e.g., in Sales or HR). Schools are understaffed and the remaining teachers are (understandably) disgruntled. There are private schools in Budapest, but they either follow weird/untested systems of education and/or are unreasonably expensive (i.e., 20% of a very good salary) compared to local salaries (they're priced to be paid by the companies of expat managers doing a stint in Budapest with their families). There is also a personal factor: having gone to regular public school in Hungary, it would feel weird and wrong sending my kid to a private school, all the while paying taxes twice (both parents). Lastly, Hungarian schools receive very little money from the government, so (like hospitals in Hungary) they are literally falling apart—in some cases, schools can't afford to buy chalk and ask parents to bring it in.

Here in Dubai, something like 80% of the population are expats who send their kids to private school because public schools are Arabic-only. Private schools are so standard that people have dropped "private" and just refer to them as schools. Schools are not inexpensive, but due to higher salaries are more affordable and cost about 10% of a good salary. Additionally, companies pick up a big chunk of the bill, so for example, I only have to pay about 20% of the tuition fee out of my pocket; the company pays the other 80%. For this, my son will go to a school with well-paid (British) teachers, lots of (South-East Asian) additional helpers and assistants, a high-quality facility with swimming pools, a very large theater, football and soccer fields, etc. As before, for elementary education, Dubai wins by a wide margin; it's a no-brainer.

Healthcare

Next to education, healthcare is the other major social service. Since my family spends most summer months in Hungary, we unfortunately interact with the hungarian health system with some regularity. In a nutshell, most facilities are like something you'd see in post-apocalyptic zombie movie. This video shows an actual, running hospital:

Obviously, not many people (doctors, nurses) want to work in such conditions, if they do they are underpaid, so hospitals are chronically understaffed. This leads to situations where many towns and cities have no hospital (closed), people wait months of years for treatment. At best, it's up to the patient to "run around" the city and find somebody who will treat them. We experienced this first-hand when my son had a case of Bell's Palsy, and we visited about 3-4 hospitals until we found a doctor who was willing to treat him. Compare this with Dubai, where we have a high-tech, world-class hospital 5 minutes away, we can walk in and see a doctor (usually educated in Europe, sometimes at the Semmelweis University in Budapest) within minutes, and the cost is negligible due to company provided insurance.

Economic opportunities

The other major factor, relevant both for my son and myself, is economic opportunities.

From 2009 I spent almost four years doing a startup called Scalien, up until late 2012 when we finally admitted failure and shut down. The story of Scalien is a long one, and I will not go into it here. The one thing that is relevant here is that, after spending years reflecting on what happened, my primary takeaway was that I should have gotten on a plane and done the startup in San Francisco—there are 100x more venture capital opportunities there, 100x more companies that would want to use any software or service that I write, etc. I see the same pattern in my wife's Hungarian company—a lot of people are working hard on the company's products, the products are great, and the company is somewhat successful in Hungary, but still, it can barely keep itself alive and pay the founders a salary. In a bigger market like the US, a company like that would probably make its founders millionaires.

The above argument can be quantified: Hungary's GDP per capita is significantly less than other countries', but I have to say, the economic opportunities for enterprising young people (and their companies) have a much bigger gap:

| Country | GDP/capita |

|---|---|

| Hungary | $18k |

| UK | $45k |

| Germany | $49k |

| UAE | $54k |

| US | $75k |

So why would I want to pin my child to Hungary and 100x limited economic opportunities? I don't want to.

Why I don't live in the US

One interesting question I get is why I don't live in the United States. The answer to this is pretty short and simple. There are two components: there is a political and an economic angle.

On the politics side, firstly, the US is usually involved in all sorts of aggression across the world to defend its own (perceived) interests through its military machine, and I don't want to support this military machine by paying taxes in the US. Second, there was a Trump presidency from 2016-2020, there could be a second in 2024, and I would not be comfortable paying taxes to be managed by a fraudster president. Third, if I were to move I would probably live in Silicon Valley, where wages are high but so are living expenses, real estate prices are unreasonably high, schools are not great, so overall, my and my family's quality of life would not be that high.

The economic angle is one about competition: in the US, especially in Silicon Valley, there are lots of people like me on the job market: smart generalists with experience at tech companies, startups, FAANGs. That makes it harder for me to get a good job and earn a high salary. In a city like Dubai on the other hand, I'm scarce—there's not a lof of people like me on the job market.

Long-term and conclusion

I often ask myself what the long-term plan is. We currently live in Dubai, but the UAE does not give out citizenship even if you live here for a very long time. You also don't get citizenship if you're born in the UAE, only if your parents are already Emiratis. Although this could change, I don't count on it—also, given that the UAE is a Muslim country, I'm not sure if I'd want that. Although, to my own surprise, I'm much more open to this option than I was in 2017 when I first started working here—back then, this would have been out of the question.

My own life experience is that it doesn't make sense for me to make long-term plans, because external factors introduce big changes. In 2011 I got married, but then in 2013 my then-wife left me completely unexpectedly and I got divorced. Any plans I had were out the window. Then in 2016 I moved to London, even though a few years before that was not an option I was considering, since I had a great time recovering from the divorce at Prezi, where I also met my current wife. When I started working at Facebook in London, I made plans to stay at least 4 years, but I ended up not liking the job or the city, and took a job in Dubai. Even one year before, if someone would have told me I will take a job in Dubai, I would have said they are crazy. Then, in Dubai, at first I really didn't like it, and I considered it a very time-limited gig. Again, if somebody would have told me that I will end up moving the entire family to Dubai, and that my son will go to nursery and kindergarten there, I would have said they are crazy. Today, I'm considering options like staying at my current job for the long-term, or taking a job in Saudi, but I also assume the most likely outcome is that my life will take an unexpected turn, since that is how it's been for the past 15 years. The most unexpected outcome would be if there is no unexpected outcome!

On the previous point it's also worth remembering that my presence in Dubai depends on various global economic and political factors. For example, tensions in the Middle East could escalate to the point where we decide to leave Dubai. Or, the economic situation could change so that it's no longer a good deal to stay, eg. if a western level taxation is introduced.

Per the above point, I don't have a specific roadmap that I'm following. Working at Majid Al Futtaim and living in Dubai is currently the best option I can identify that is available to me. I am open to other opportunities, both in Dubai, and in other interesting places such as Saudi, as long as the regional political and economic situation is favorable. I hope to retire by age 50 from working for someone else, work remotely on projects I choose, and perhaps live a follow-the-sun model, spend winter in Dubai and summer along the Switzerland-Italy-Croatia axis, to the degree that my son's schooling schedule allows.

Lastly, sometimes people tell me, "But Marton, if you lived in Hungary, you could just ignore politics and you can afford private schooling and healthcare". This is not true: I can't just ignore bad politics, and to me, this deal doesn't add up. In this scenario, I'd earn a significantly lower gross salary (not anybody's fault) and I'd pay a total tax rate of about 50% (combined income tax, other contributions, and 27% VAT when I spend what is left). This means from January to June I'd effectively be working from Viktor Orbán, in the sense that he distributes my taxes among parts of the state that he manages, while he misappropriates some portion. And then, out of the 50% that is left, I'd pay for private schooling, private healthcare, both of which are still relatively low quality, while I drive on poor quality roads and deal with half the populations spewing hate speech and believing in alt-right conspiracies. No, thanks!

I ❤️ Hungary, I just don't want to live there.

PS: I have a lot of friends in Dubai who are from countries that are dealing with significantly more serious challenges than Hungary, for example Lebanon or Ukraine. I acknowledge that the issues in Hungary I write about here are "1st world problems" compared to the security, economic and political situation in countries such as those.